This essay was submitted in 2023 as coursework toward a Master of Science degree in Sustainable Development. All work belongs to the website author. Title image by icalvinhsu from Pixabay.

“History will judge us harshly if we fail to protect the world’s last large and unique wilderness”

(Hogg et al., 2020)

Introduction

The increasing popularity of nature-based tourism is perhaps best exemplified by the precipitous growth in tourism to Antarctica. In the 2022-23 season almost 105,000 tourists visited, a figure that has nearly tripled in just eight years and increased sixteen-fold since 1991-92 (ASOC, 2023; Bastmeijer et al., 2023). Preliminary estimates for the 2023-24 season predict further increases, to over 117,000 visitors (IAATO, 2023a). At the same time, accelerated melting of glaciers and surface ice due to fast-increasing temperatures has threatened polar ecosystems like never before, resulting in the continent becoming what is referred to as a ‘last-chance tourism’ destination (Cajiao, 2022).

Antarctica is a unique destination; there is no permanent population or national jurisdiction. Governance is provided under the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO), and coordination of tourism industry players is managed by the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO). Founded in 1991 by 7 US-based tour companies, today over 100 tourism businesses operating on or around the continent (nearly all companies active in the market) are IAATO members (IAATO, 2023b; Weber, 2012).

This essay will evaluate the IAATO’s operations by drawing from the sustainable business model (SBM) and circular economy (CE) frameworks. It will begin with an overview of the state of Antarctic tourism and the environmental impacts attributed to it. This will be followed by a description of the IAATO’s mission statement and operations with a particular focus on environmental sustainability, and identification of pollution and growth management as the most significant issues facing the association. Next, it will analyze more deeply the IAATO’s actions in these areas and offer some observations on where improvements could be made. Finally, it will offer recommendations for how the IAATO might sharpen its sustainability focus, and in doing so improve its sustainability performance.

The state of Antarctic tourism and its impacts

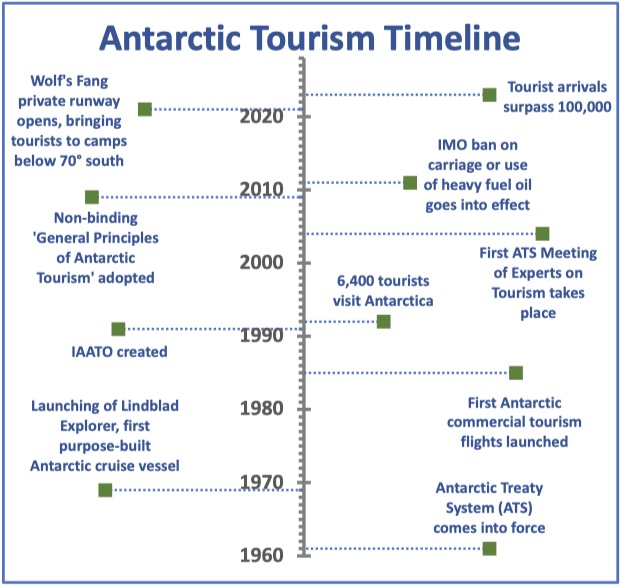

Over 90% of Antarctic tourists arrive by ship, the majority of which are small vessels with a capacity of less than 500 passengers; the remainder arrive by plane to then undertake ship- or land-based tours or arrive on private yachts (ASOC, 2023; Bastmeijer et al., 2023). In recent years the number of landing sites and activities offered by tour operators have increased significantly, and the tourism season has been extended as well (Bastmeijer et al., 2023). On land, new seasonal lodgings have been constructed, including a luxury campsite with its own private runway where guests can fly in and partake of various adventure and wildlife-watching activities (Beldi, 2021). The development of tourism in Antarctica has progressed very quickly; the timeline below helps places some of the key Antarctic tourism developments into temporal context.

Environmentalists are increasingly raising the alarm about tourism’s impact upon the sensitive Antarctic terrestrial and marine ecosystems. The Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC) highlights three impacts as the most concerning: black carbon (BC), black/gray water, and fragile ecosystems/invasive species (ASOC, 2023). Table 1 below defines and highlights some examples of these concerns.

Table 1

Concern | Definition/Additional information | Example |

BC | Soot produced when fossil fuels burn | BC emitted from ships and airplanes has darkened the snow in affected areas, causing accelerated snowmelt and shrinkage of the snowpack (Cordero et al., 2022) |

Black/Gray water | Black water (sewage) discharge from ships is somewhat regulated; gray water is not | A study evaluating water samples from various locations on/near the Antarctic peninsula found high-risk levels of substances such as analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs in wastewater discharged from ships and land-based settlements (Olalla, Moreno and Valcárcel, 2020) |

Fragile ecosystems/ invasive species | Small and ecologically sensitive ice-free areas where the highest concentrations of both biodiversity and tourists are located; invasive species can be introduced | Invasive species can be introduced through pathways such as tourists’ clothing and personal equipment, as well as on the hull and through intake ports and ballast water of ships (Hughes, et al., 2020) |

IAATO operations – overview and challenge identification

The IAATO’s stated vision is that “Through self-regulation, Antarctic tourism is a sustainable, safe activity that causes no more than a minor or transitory impact on the environment and creates a corps of ambassadors for the continued protection of Antarctica.” (IAATO, 2023b). It also offers a more detailed 10-point mission statement, which can be found in Annex A along with my categorizations of each of the ten points.

The IAATO operates as a voluntary, self-regulating industry association. Companies first join as provisional members and only receive full membership after conducting an environmental impact assessment and meeting a specific set of operating standards, with in-person/on-board monitoring requirements during the provisional period. Some of the latest environmental standards put in place since 2019 include new and expanded timed geofencing of areas where significant whale presence has been noted, including a mandatory 10-knot speed limit implemented to reduce strike risks. Other operational conditions listed in IAATO Bylaws include landing restrictions based on vessel capacity (vessels with >500 passengers may not land), rules for how many visitors are allowed ashore at one time (maximum 100), minimum staff-to-visitor ratio while ashore (1:20) and the requirement to coordinate site visits via the IAATO Ship Scheduler to avoid multiple ships landing in the same place at the same time. Members are also expected to inform their guests of the various Visitor Site Guidelines and ensure compliance (IAATO, 2023c). While these actions go some way towards mitigating the ecosystem/invasive species challenge, they do little to address the concerns of BC and black/gray water.

The IAATO works within a challenging operational environment, where both its authority and that of the ATS are limited to their members, allowing non-member parties to freely use Antarctica’s resources without legal hindrance (Lamers, 2009). Yet the association has received near-universal praise for its strong efforts at self-regulation and its collaborative activity with scientific institutions (Bastmeijer et al., 2023; Chan, 2020; Lamers, 2009; Palmowski, 2021). According to Palmowski (2021), “Antarctic tourism is today’s best managed tourism sector in the world..” (p. 1526). However, the same author raised concerns about the ability of the IAATO and the ATS to continue their success in a very fast-growing and dynamically developing sector. The association’s growth (it welcomes 2 to 5 new members each year) also risks making self-regulation of a common pool resource more challenging (IPTRN, 2021; Lamers, 2009).

From this initial review of the state of Antarctic tourism and the IAATO, two pressing environmental issues facing the association emerge: (1) the pollution caused from fossil fuel burning and wastewater discharge, and (2) explosive growth of the post-pandemic Antarctic tourism sector, which threatens to overwhelm even the most effective of sustainability measures. The following section will more deeply evaluate the IAATO’s response to these challenges and opportunities for improvement.

Reducing pollution

IAATO initiatives to address Antarctic tourism pollution, primarily from wastewater discharge and fossil fuel used to power ships and other motorized transport, have been quite limited to date. The limit on cruise ship passenger loads is notable, but other pollution reduction measures have yet to be applied. In October 2022, the association published an article on its website indicating that its members were requested to submit fuel consumption data after the 2022-2023 season “as part of a unanimous pledge to create a climate change strategy for Antarctic tourism” (IAATO, 2022). Its Information Paper recapping the 2022-23 season and looking ahead to 2023-24 made no mention of the results, however, nor were any initiatives concerning fuel consumption, emissions or waste included in the document (IAATO 2023a).

To analyze IAATO (in)action towards reducing pollution, we begin by recalling Stubbs and Cocklin’s (2008) observations about SBM’s, including that they treat nature as a stakeholder and consider all stakeholder needs rather than only those of their shareholders. As a voluntary association dependent upon its members, the IAATO has tended to focus on measures which are less economically impactful to its membership (implementing a ‘techno-fix’ to schedule shore visits, placing responsibility on individual tourists through site guidelines and the ambassador program) rather than on those which, although they would create considerable value for the environment, would demand more of tour/cruise operators based on a strongly sustainable definition of value. Thus, we observe that when it comes to the formidable challenge of reducing pollution, the IAATO has tended to follow shareholder expectations, adhering to Upward and Jones’ (2016) description of a ‘thin’ definition of value as one referencing “only (and implicitly) the economic (marketplace) as a system boundary of concern” (p. 105).

To improve upon its goal of having ‘only a minor or transitory impact’, the IAATO could benefit from embracing some of the CE principles regarding renewables, wastewater management and energy recovery from waste. While the CE framework is more typically applied to packaging or manufacturing, many of the features highlighted by Murray, Skene and Haynes (2017) in their conceptual review – reducing consumption and pollution, improving resource productivity and eco-efficiency – can all be applied to a cruise or isolated tourism operation. Indeed, the idea of a ‘closed-loop economy’ in such operations perhaps offers a useful analogy of the goal of keeping (in the case of a cruise ship) waste and pollutants onboard, with no impact on the ecosystem (ibid). IAATO member Ponant Cruises has shown that this way of thinking can go a long way towards achieving that goal; their recently launched ship Le Commandant Charcot employs hybrid propulsion (liquefied natural gas and electric batteries), has outdoor benches heated by exhaust fumes recovery, its own on-board desalination system for drinking water, and an advanced wastewater treatment system with waste storage capacity sufficient to ensure that no discharges are needed during its cruise journeys (Ponant, 2023).

Managing growth

The IAATO’s growth management efforts thus far have consisted of attempts to mitigate the impacts of growth rather than addressing it directly through limitations on visitor numbers or activities. This is perhaps not surprising when one considers that a majority of the association’s funding comes from visitor fees paid by operators ($3.50/person/day for the 2022-23 season) (IAATO, 2023d), which means that the IAATO budget is directly connected to tourist arrivals and thus incentivizes growth. This circumstance poses a significant barrier for the association to take meaningful action towards managing growth, as their financial stability is dependent upon an economic growth model. Evans et al. (2017), however, remind us that creating value in an SBM requires a more holistic perception that also weighs social and environmental goals.

The evidence is clear that unconstrained growth of Antarctic tourism has serious negative impacts on its sensitive ecosystem, impacts which can only be partially mitigated by incremental improvements. We also recall, however, that the IAATO’s structure as a voluntary association in effect run by its members precludes it from unilaterally imposing visitor number limits. Considering these circumstances, again Stubbs and Cocklin (2008) offer useful insight through their observation that a successful SBM is not accomplished only at the firm level, but through the efforts of the whole system to operate sustainably. In addressing this challenge, therefore, the IAATO must collaborate with other stakeholders, including governing bodies, the scientific community, and Antarctic ambassadors to plan and implement an SBM targeted to sustainably managing growth.

Recommendations and Conclusion

While the IAATO is limited in its power to exert control over its members or create legally binding rules, there are some actions it can take to improve its sustainability performance and encourage its members and other stakeholders to do the same.

- Offer reward-based incentives for operators taking measurable steps to reduce pollution: the IAATO does not have a mandate to require pollution reduction measures, but through the Ship Scheduler program it could offer preferential landing site access to vessels which meet specific (challenging but realistic) criteria for fuel consumption, wastewater treatment, etc. It can also work with governance authorities to implement further regulatory restrictions, as was done with the IMO heavy fuel oil ban (Jainchill, 2010).

- Decouple IAATO funding from industry growth: the current funding structure incentivizes the IAATO to support growth in tourism numbers, which runs counter to its mission of sustainability, ‘minor or transitory’ environmental impact, and protection of the Antarctic. IAATO members pay dues, which as one possible solution could be increased and tied to each operator’s market share rather than volume; the higher dues would replace the per visitor fee, creating a funding structure which is not connected to sector growth, nor penalizes new entrants or smaller operations.

- Work with system stakeholders (governing bodies in particular) to explore the development of a system of tradable permits to limit visitor numbers: this would function similarly to existing carbon cap-and-trade schemes. The feasibility and possible characteristics of such a system are currently being evaluated from both a research and policy standpoint by a group of academics from the Netherlands, who envision dual goals of capping tourist numbers and generating revenue for conservation (IPTRN, 2021). Such a system could also connect with the funding structure changes suggested above.

The IAATO has thus far managed to navigate a challenging legal and operational environment to establish itself as a highly regarded industry association. If it hopes to hold onto its influential position and achieve the goals set out in its Mission Statement, it must work with its members and system stakeholders to recognize and address the changes happening around it.

Annex A: IAATO Mission Statement | ||

1 | Advocate and promote the practice of safe and environmentally responsible travel to Antarctica | Environmental/Safety |

2 | Operate within the parameters of the Antarctic Treaty System, along with IMO Conventions and similar international and national laws and agreements | Legal |

3 | Have no more than a minor or transitory impact on the Antarctic environment | Environmental |

4 | Foster continued cooperation among our members | Industry |

5 | Provide a forum for the international private-sector travel industry to share their expertise, opinions, and best practices | Industry |

6 | Create a corps of ambassadors for the continued protection of Antarctica by providing the opportunity to experience the continent firsthand | Social/Educational/ Environmental |

7 | Support science in Antarctica through cooperation with National Antarctic Programs, including logistical support and research | Scientific |

8 | Foster cooperation between private-sector travel and the international science community in the Antarctic | Industry/Scientific |

9 | Ensure our members employ the best qualified staff and field personnel through continued training and education | Educational/Industry |

10 | Encourage and develop international acceptance of evaluation, certification and accreditation programs for Antarctic personnel | Industry |

Source: IAATO (2023b); categories developed by author | ||

Bibliography

ASOC (2023) Responsible Tourism and Shipping. Available at: https://www.asoc.org/campaign/responsible-tourism-and-shipping/ (Accessed: 17 October 2023).

Bastmeijer, K., Shibata, A., Steinhage, I., Ferrada, L.V. and Bloom, E.T. (2023) ‘Regulating Antarctic tourism: the challenge of consensus-based decision-making’, American Journal of International Law, pp.1-27. doi: 10.1017/ajil.2023.34.

Beldi, L. (2021) ‘Luxury tourism is landing in Antarctica — but at what cost?’, ABC News [Online]. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-12-17/luxury-tourism-is-landing-in-antarctica-but-at-what-cost/100682698 (Accessed 10 October 2023).

Cajiao, D. et al. (2022) ‘Tourists’ motivations, learning, and trip satisfaction facilitate pro-environmental outcomes of the Antarctic tourist experience’, Journal of outdoor recreation and tourism, 37, p. 100454–. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2021.100454.

Chan, K. (2020) ‘Antarctic Sustainability: Regulations and measures from IAATO and Expedition Cruise Operator’, Environment, Resource and Ecology Journal, 4(1), pp.62-65. doi: 10.23977/erej.2020.040109.

Cordero, R.R. et al. (2022) ‘Black carbon footprint of human presence in Antarctica’, Nature communications, 13(1), pp. 984–984. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28560-w.

Evans, S., Vladimirova, D., Holgado, M., Van Fossen, K., Yang, M., Silva, E. A. and Barlow, C. Y., (2017). Business model innova5on for sustainability: Towards a unified perspec5ve for crea5on of sustainable business models. Business Strategy and the Environment. 26(5), pp. 597–608.

Hogg, C.J. et al. (2020) ‘Protect the Antarctic Peninsula – before it’s too late’, Nature (London), 586(7830), pp. 496–499. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02939-5.

Hughes, K.A. et al. (2020) ‘Invasive non‐native species likely to threaten biodiversity and ecosystems in the Antarctic Peninsula region’, Global change biology, 26(4), pp. 2702–2716. doi:10.1111/gcb.14938.

IAATO (2022) ‘Antarctic Tour Operators’ Fuel Consumption to be Analysed as They Embark on Climate Strategy’, IAATO Newsroom, 6 October. Available at: https://iaato.org/antarctic-tour-operators-fuel-consumption-to-be-analysed-as-they-embark-on-climate-strategy/ (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

IAATO (2023a) ‘IAATO Overview of Antarctic Vessel Tourism: The 2022-23 Season, and Preliminary Estimates for 2023-24’, XLV Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting, 29 May-8 June. Available at: https://documents.ats.aq/ATCM45/ip/ATCM45_ip056_e.docx (Accessed: 17 October 2023).

IAATO (2023b) Our Mission. Available at: https://iaato.org/about-iaato/our-mission/ (Accessed: 14 October 2023).

IAATO (2023c) IAATO Bylaws. Available at: https://iaato.org/about-iaato/our-mission/bylaws/ (Accessed: 19 October 2023).

IAATO (2023d) How We’re Funded. Available at: https://iaato.org/about-iaato/funding/ (Accessed: 20 October 2023).

International Polar Tourism Research Network (IPTRN) (2021) ProAct Webinar 15 April. Available at: https://sites.google.com/view/polartourismresearch/knowledge-commons/proact-webinar?authuser=0 (Accessed: 17 October 2023).

Jainchill, J. (2010) ‘Heavy-fuel ban in Antarctica expected to shut out large cruise ships’, Travel Weekly [Online]. Available at: https://www.travelweekly.com/Cruise-Travel/Heavy-fuel-ban-in-Antarctica-expected-to-shut-out-large-cruise-ships (Accessed: October 23, 2023).

Lamers, M. (2009) The future of tourism in Antarctica: challenges for sustainability. Doctoral Thesis. Maastricht University. Doi:10.26481/dis.20091112ml.

Murray, A., Skene, K. & Haynes, K. (2017) The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. Journal of Business Ethics. 140 (3), 369–380. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2.

Olalla, A., Moreno, L. and Valcárcel, Y. (2020) ‘Prioritisation of emerging contaminants in the northern Antarctic Peninsula based on their environmental risk’, The Science of the total environment, 742, pp. 140417–140417. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140417.

Palmowski, T. (2021) ‘Development of Antarctic Tourism’, Geo Journal of Tourism and Geosites, 33(4), pp. 1520–1526. doi:10.30892/gtg.334spl11-602.

Ponant (2023) What makes Le Commandant Charcot so remarkable? Available at: https://escales.ponant.com/en/le-commandant-charcot-unique-ship/ (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

Stubbs, W. and Cocklin, C. (2008) ‘An ecological modernist interpretation of sustainability: the case of Interface Inc’, Business strategy and the environment, 17(8), pp. 512–523. doi:10.1002/bse.544.

Upward, A. and Jones, P. (2016) ‘An Ontology for Strongly Sustainable Business Models: Defining an Enterprise Framework Compatible With Natural and Social Science’, Organization & environment, 29(1), pp. 97–123. doi:10.1177/1086026615592933.

Weber, M. (2012) ‘Cooperation of the Antarctic Treaty System with the International Maritime Organization and the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators’, Polar journal, 2(2), pp. 372–390. doi:10.1080/2154896X.2012.735045.